Senator David Pocock – Tabled documents by Nigel Carney alleged mismanagement and wrong doing – Murujuga Rock Art Monitoring Program.

Senator Lidia Thorpe tabling of Statement of Nigel Carney concerning alleged Murujuga Rock Art Strategy corruption – July 2023

Further information:

Leaked letter reveals internal concerns about science on Australia’s next world heritage site

Woodside’s Pluto trucking contract shocks Pilbara traditional owners

Murujuga Heritage Delay Indicates Govt-Gas Industry Collusion

Burrup Peninsula: Embarrassing reason ancient Indigenous site won’t be listed on the World Heritage register

Gas plants expand while ancient Murujuga rock art waits on modern science

Pilbara gas-fuelled fertiliser plant gets $6b green light, but rock art concerns remain

WA awards new contract to safeguard Burrup rock art for World Heritage bid

Puliyapang Pty Ltd appointed to monitor Murujuga rock art

PETROGLYPHS ON MURUJUGA, WESTERN AUSTRALIA – UNIQUE, ENDANGERED AND DISAPPEARING – THE R.G. BEDNARIK LEGACY FOR HOPE

Abstract: The petroglyphs on Murujuga in northwest Western Australia are unique and Murujuga is regarded by many as the most important prehistoric rock art site in the world. The petroglyphs continue to be endangered and damaged by huge industrial developments and emissions of acid forming gases and nitrogenous compounds. Robert G Bednarik has dedicated his life to documenting the petroglyphs, understanding the chemistry of the ferromanganese rock surface patina and how industrial emissions are destroying the rock art. Most of all, Bednarik has been a towering advocate for removing industry from the area. His efforts and optimism continue today.

Introduction

The petroglyphs on Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula) in northwest Western Australia are unique in the world (Bednarik 2006a; Lorblanchet 2018; Mulvaney 2022). Nowhere else does there remain for all to see today, encapsulated in the rock engravings of Murujuga, potentially 45,000 to 65,000 years of the culture and spiritual beliefs of humankind continuously created through vastly changing environments. The petroglyphs on Murujuga are an unsurpassable tribute to the oldest continuing living culture in the world. They are priceless and irreplaceable. Michel Lorblanchet, the first archaeologist to describe the rock art on Murujuga, recently stated in correspondence ‘To my archaeological opinion, Murujuga rock art site is the most important site in the world. ……

During my life I studied rock art sites in France and in different other countries and I never found sites as important as Murujuga.’ Murujuga is also the site of a huge industrial complex. An iron ore export terminal was established in 1964 and a salt production facility in 1968. Natural gas processing facilities commenced in the early 1980s and were followed by liquefied natural gas production plants in 1995 and 2007. An ammonium fertiliser plant commenced production in 2006 and an ammonium nitrate production facility in 2017.

The Australian National Pollution Inventory shows that in 2021-22 the Woodside Energy Limited Burrup gas plants produced annually 9,000 tonnes (t) oxides of nitrogen, 120 t sulphur dioxide and 16,000 t of volatile organic compounds, while the Yara Pilbara fertiliser plants produce another 1,000 t of nitrogen dioxide. The Port of Dampier is one of the busiest bulk-handling ports in the world. During the 2021-2022 were 3,324 vessels entered the port with exports over 160 million t. A single bulk cargo ship burning high-sulphur fuels has been estimated to release 5200 t of sulphur oxides into the atmosphere annually, although since 2021, ships entering Australian ports are to use low sulphur fuel. Nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide form strong nitric and sulphuric acids when mixed with water and air.

There is now undeniable proof the petroglyphs on Murujuga are being degraded by industry and that the outer ferromanganese patina, essential for survival of the petroglyphs, is being dissolved by mineral acids and organic acids from bio-organisms stimulated by the huge nitrogen compound deposition on the rock surfaces (Smith et al. 2022a, Smith et al. 2022b). The fact that we now know the petroglyphs are in such danger of destruction can be traced back to the many earlier activities of Robert Bednarik. Bednarik was one of the first people to realise the extent and significance of the rock art on Murujuga.

He recognised the danger industry would pose to the petroglyphs through physical damage and atmospheric emissions. Bednarik made sure he understood the chemistry of the ferromanganese patina and how it would be destroyed by inorganic and organic acids. In addition, Bednarik was an unrelenting advocate for saving the petroglyphs by arguing to governments, industry bosses, academics and others, that industry should not be placed on Murujuga. Bednarik’s advocacy was largely responsible for bringing the attention of the public to the plight of the petroglyphs and encouraged the formation of groups such as the Australian Rock Art Research Association for research and Friends of Australian Rock Art to continue public advocacy and protests. The most striking aspect of Bednarik in his efforts to save the Murujuga petroglyphs, is his enormous capacity to read and understand the relevant issues of the day and to communicate these and their possible solutions through prodigious writing to the scientific community and to the public.

Recognition of the significance of Murujuga petroglyphs

Robert was born in Austria in 1944 and became interested in petroglyphs in 1963 when he ‘discovered’ rock art in limestone caves in Vienna. When industrial development on Murujuga was mooted in the early 1960s, several staff from the Western Australian Museum including Ian Crawford made a brief visit to the area following their detailed work on Depuch Island. Soon after, other museum staff from the Department of Aboriginal Sites, including Peter Randolph, Vera Novak, John Clarke and Bruce Wright went to Murujuga to start documenting the rock art (Mulvaney 2022). Bednarik recalls that in 1965, he read an Australian newspaper article indicating a lack of archaeological research in northwest Australia. Being an autodidact and enthused by rock art, Bednarik decided to travel to Australia to study the rock art, arriving in Dampier in November 1967 (Bednarik 2006a).

He was employed as a Project Manager for a company servicing the mining industry at Dampier (Vinnicombe 2002). Bednarik started photographing and recording petroglyphs on Murujuga, but also spent considerable time studying Aboriginal sites at another Pilbara location undergoing mining development at Mount Tom Price (Bednarik 1977). During these early years, Bednarik worked closely with Traditional Aboriginal Knowledge Holders to better understand the significance and meaning of the rock art motifs. Bednarik’s activities complemented those of Enzo Virili, employed by Dampier salt from 1970 to 1974, and Warwick Dix from the Western Australian Museum in documenting petroglyphs on Murujuga (Virili 1977).

A description of the Murujuga petroglyphs was presented at the first Australian conference on rock art, held in Canberra in 1974 and sponsored by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. These discussions in Canberra brought the significance of Murujuga petroglyphs to a wider audience, which resulted in the employment by the Australian Government of the French archaeologist, Michel Lorblanchet, to undertake archaeological studies on Murujuga in 1975-76 and again in 1983-84 (Lorblanchet 1983, 1992, 2018). South African rock art specialist, Patricia Vinnicombe, came to Australia to work with Aboriginal people in the Pilbara region who were still creating pictographs and petroglyphs and could interpret rock art. She was subsequently employed by the Western Australian Department of Aboriginal Sites and the Museum to document petroglyphs on Murujuga in advance of the encroaching industry (Vinnicombe 2002). During this time, she photographed and described many petroglyphs and produced a formal inventory of Murujuga rock art, which include photographs from Bednarik’s collection.

Impact of industry on the petroglyphs

Bednarik became fascinated by the outer, thin surface layer of rocks, frequently called the patina, or desert varnish in arid areas of the world. The Murujuga petroglyphs were formed by breaking through the outer brown/red/black patina and removing some of the underlying orange/yellow weathering rind to form a colour and contour contrast. Loss of the patina either through dissolution or flaking destroys the petroglyphs. Bednarik put great effort into understanding the composition of the patina of different types of rocks around the world and speculated on its formation, particularly the influence of environmental pH (Bednarik 1979, 1980). He concluded that the ferromanganese patina found in arid environments would only form under alkaline to neutral environments. Murujuga is a dry desert environment. Bednarik (2002) reported that rainwater at Dampier on Murujuga had a pH around 7.0 with a range of 7.6 to 6.5 in the 1960s prior to industrialisation of the area. Bednarik (2002) commented ‘This [ferromanganese] patina is highly susceptible to even minor downward fluctuations in ambient environmental pH, especially in the range from pH 7 to 6’.

Bednarik (2002) estimated the huge amount of nitrogen dioxide (5,800 t/y) and sulphur oxides (120 t/y) that were being produced by the then existing natural gas treatment facilities on Murujuga. He understood these gases would be deposited on Murujuga rock surfaces and form nitric and sulphuric acids when exposed to water and air. Bednarik (2002) estimated that the amount of acidic forming emissions being produced on Murujuga were greater than for the whole of the Perth metropolitan area. He used basic chemistry to conclude that the nitric and sulphuric acids would dissolve the outer ferromanganese patina and destroy the rock art over time.

Bednarik (2002) reports that between early petrochemical industrial development in 1988 and 2001, there was noticeable ‘bleaching’ of rock surfaces, which he claimed to confirm through mathematical analysis of colour changes in photographs he had taken over time. Bednarik’s (2002) microscopic observations showed the rock surfaces had become ‘superficially friable’, with the amorphous silicate skeleton becoming more prominent in the patina as the iron and manganese compounds were dissolved. Bednarik suggested that the rock patina mass may be reduced by <5% to 30% at different places, but emphasised the large variation across rock patina in all measurements.

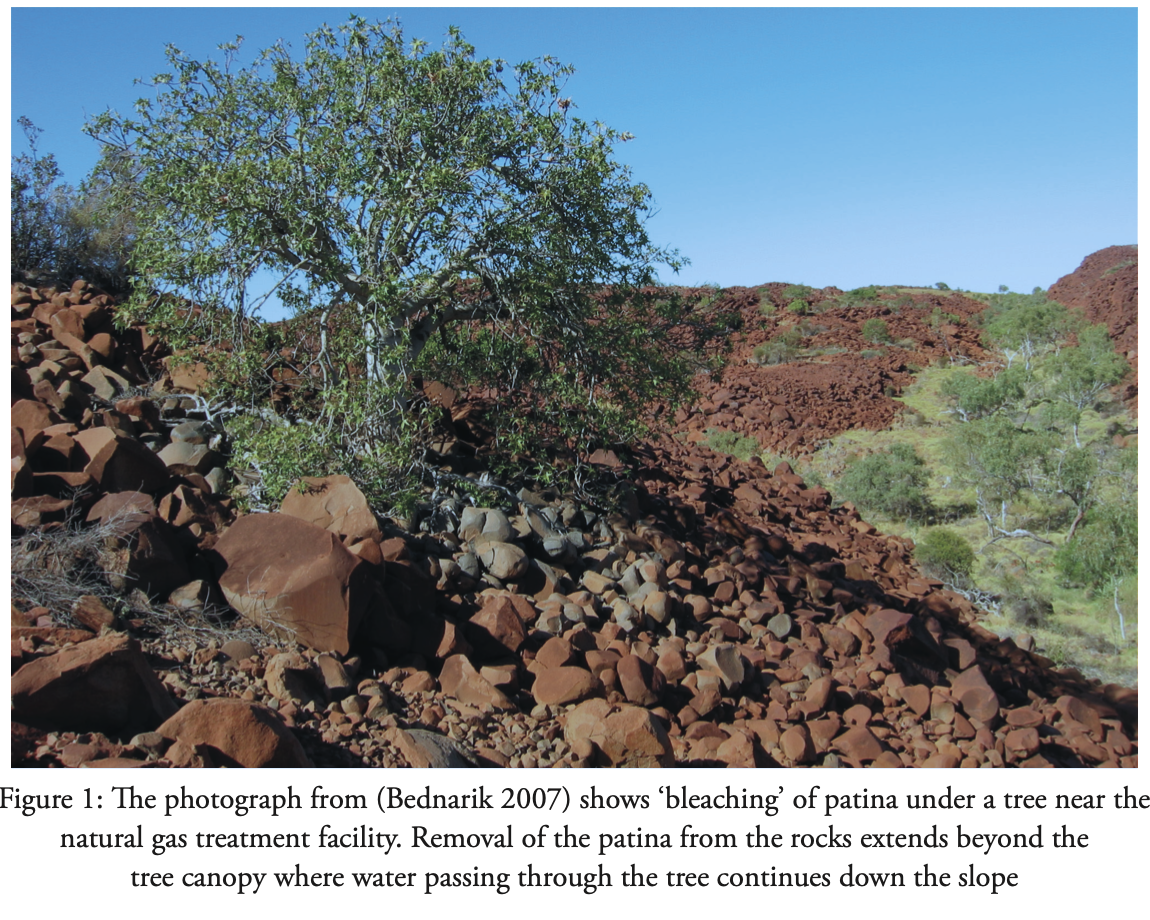

Bednarik (2007) suggested that because of the very low rainfall on Murujuga, tree canopies can retain large amounts of the dry deposits of nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide because of their many layers of foliage. Rainwater falling through the foliage concentrates these acid forming chemicals beneath the trees. Bednarik (2007) collected the ‘through-fall’ rain under trees at sites on Burrup Peninsula in 2004 and found it to be highly acidic with pH as low as 3.2. He found complete removal of the rock patina below a tree adjacent to the natural gas facility where the low-pH 3.2 rain was collected (Fig. 1).

Bednarik (1979, 2002) also showed that the patina was completely removed from Murujuga rocks where birds frequently perched. He found that the mean pH was 5.9 across 30 sites on Murujuga where the rock patina had been dissolved by bird droppings. These conclusions by Bednarik from his early observations that industrial development would physically damage many petroglyphs. His conclusion that a small drop in rock surface pH would dissolve the Murujuga rock patina has proven to be prophetic.

Thousands of rocks with petroglyphs were removed in the early 1980s and 2000s for development and expansion of the natural gas operations (Bednarik 2006b). These rocks were seen by the Western Australian government to be the government’s responsibility and directed Ian MacLeod, a corrosion specialist at the Western Australian Museum, to study changes that industry may be having on the rock surface chemistry. MacLeod (2005) found that the pH of rock surfaces near the gas treatment facilities had fallen from near neutral (pH 6.8±0.2) pre-industry to less than 4. MacLeod (2005) stated that: ‘the most acidic rock (pH 3.58) … was found down in a gully downwind a few hundred metres from the gas production facility’.

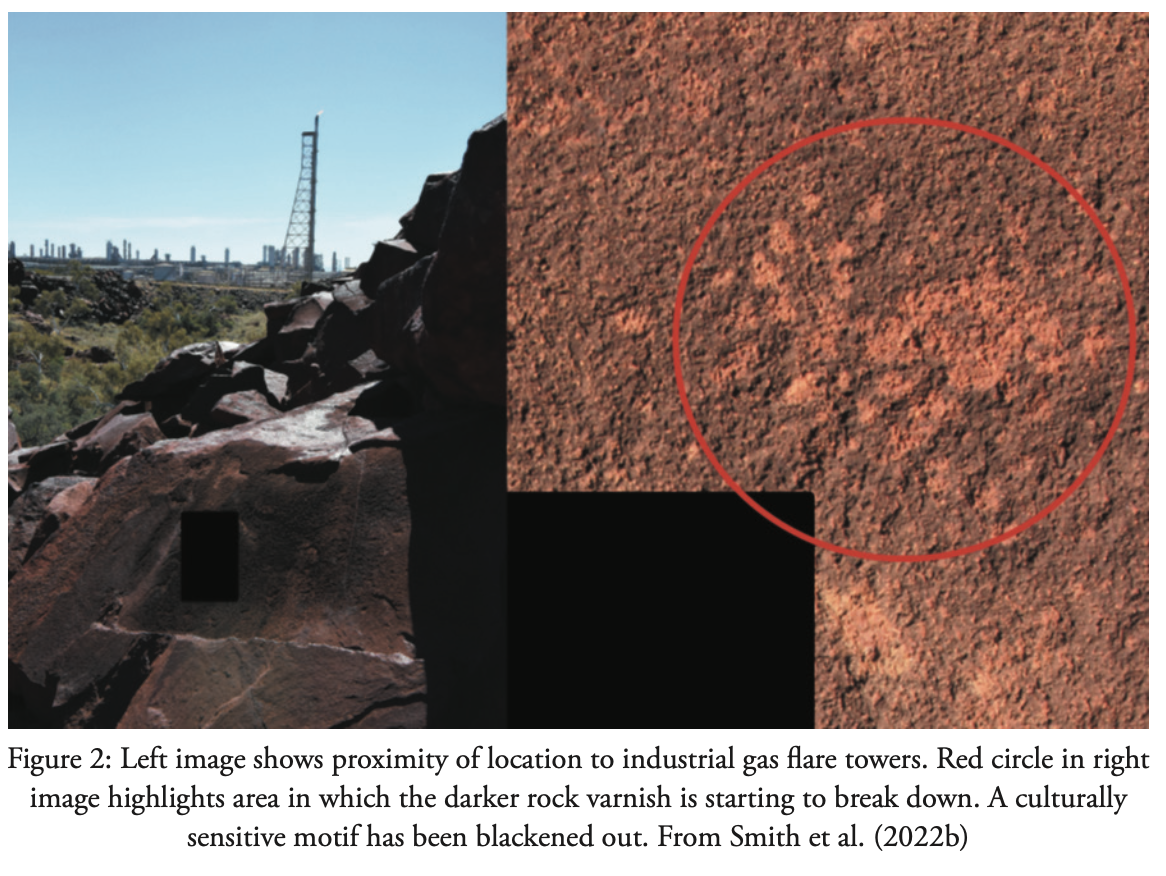

Critically, MacLeod (2005) showed that, as the rock surface pH falls, there was a logarithmic increase in the dissolution of manganese and iron ions, confirming Bednarik’s speculation. Subsequently, theoretical (Black et al. 2017b) and empirical (Smith et al. 2022b) research has confirmed Bednarik’s views that the rock surface patina on Murujuga has become lighter and redder in colour and the patina is degrading on rocks with petroglyphs (Fig. 2).

Research within the Murujuga Rock Art Conservation Project at the University of Western Australia has also confirmed that dissolution of manganese from the patina of granophyre and gabbro rocks from Murujuga commences when patina pH falls below 6.10 (5.97-6.22: 95% confidence limits) for granophyre and pH 6.50 (6.01-7.09: 95% confidence limits) for gabbro. Again, these experimental results confirm the proposition by Bednarik (2002) that the critical pH for dissolution of the Murujuga rock surface patina was between pH 6 and pH 7.

Advocacy

Bednarik has been and continues to be a prodigious advocate for the Murujuga petroglyphs. In his writings, he succinctly outlines his concerns about industrial development and its impacts on the rock art, and he almost always provides a potential solution to the issues raised. From his earliest writings, Bednarik realised the importance of research to be undertaken on Murujuga to provide empirical evidence for his speculations (Bednarik 1979). He was instrumental in establishing the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA) in October 1983. The Association commenced immediately the Journal Rock Art Research, with Robert Bednarik as editor and its first edition appeared in 1984.

Bednarik was also responsible for production of the Journal and continues to hold these positions today, with two volumes of the Journal being produced each year. Bednarik writes an Editorial piece for each volume covering many of the perceived issues currently relating to rock art around the world. Bednarik and AURA were responsible for organising the first international academic conference dedicated entirely to the study of prehistoric rock art, held in Darwin during September 1988. The International Federation of Rock Art Organisations was established at this 1988 Darwin Conference. AURA also established a Newsletter in 1986 to cover topics concerning rock art for a wider audience and to outline activities of AURA. This Newsletter continues today covering international rock art issues and is still edited by Bednarik.

Advocacy for research

It was through Bednarik’s agitation and publications that the Western Australian government decided in 2002 to establish a four-year research program to determine the processes causing deterioration of the petroglyphs through industrial emissions (Bednarik 2004). The research program was supervised by the Burrup Rock Art Monitoring and Management Committee (BRAMMC)

and tenders were given for measuring and modelling of pollutants in the air (Gillett 2008), microbiological studies at Murdoch University (O’Hara 2006) and colour change measurements and gas fumigation studies by CSIRO (Lau et al. 2008). Bednarik (2004) was particularly critical of the colour measurement techniques and fumigation tests to be used by CSIRO. He warned the research would be ‘four years of unfocused and purposeless gathering of probably meaningless data’ and ‘I predict that the results of this project in 2008 will be inconclusive and unreliable, and that the main finding will be that CSIRO will require further funding to continue the work’. ‘Meanwhile the government expects to continue its destruction of the Dampier rock art, bulldozing many more sites, and permitting the huge petrochemical industries to belch out ever more acidic emissions, at the rate of tens of thousands of tonnes per year.’

These predictions were proved to be exactly correct. The CSIRO colour measurements continued until 2016, with the claims to 2014 that there were no impacts of industry on the rock art and ‘there is no consistent trend for colour change in an increasing or decreasing direction’ (Markley et al. 2015). However, as Bednarik postulated, the results proved to be totally useless because of unsuitable techniques, lack of statistical analysis and false interpretation (Black and Diffey 2016; Black et al. 2017a). The measurements were found to be so unreliable that the results were deemed not to be useful (Data Analysis Australia 2017). In the meantime, the Western Australian government continues to this day to encourage more industrial development on Murujuga (Smith et al. 2022b).

Public advocacy

Bednarik has always been outspoken about the uniqueness of Murujuga rock art and the damage that results from industrial development and emissions (Mulvaney 2022). Partly, as a result of his agitation, a local group of people from the Karratha and Districts Chamber of Commerce led by Gary Slee and including Traditional Elder, Wilfred Hicks, formed the Champions of Burrup Rock Art (COBRA) in the early 1980s to educate the local community and to protest and to lobby the local and state governments to stop further industrial development on Murujuga (Slee 2022). COBRA then morphed in 2006 into a larger national organisation, Friends of Australian Rock Art (FARA), formed by the Australian Greens politician, Robin Chapple, and the organisation’s current convenor, Judith Hugo, from 2007. FARA arranged hugely successful protests all around the world with their ‘Stand up for the Burrup’ campaign to further bring the attention of the world to the plight of Murujuga petroglyphs. FARA continues to protest and make submissions to governments and industry in an endeavour to protect the Murujuga petroglyphs.

Bednarik (2002) had advocated for the non-industrial land on Murujuga to be made into a National Park. The lobbying of Traditional Owners, FARA, AURA, the Western Australian National Trust and Bednarik resulted, in 2007, in the declaration of National Heritage Listing by the Australian government of 44 percent of the Murujuga peninsula and all of the remainder of the Dampier Archipelago. The National Heritage listing resulted in the Australian government, as well as the state government, having power over deciding on the establishment of new industry on Murujuga and the conditions set for industrial operations. Unfortunately, the additional consideration by the Australian government has had little impact on reducing industrial development or emissions on Murujuga.

Bednarik, along with AURA, the National Trust of Western Australia Robin Chapple and Ken Mulvaney, in 2004 were responsible for having Murujuga added to the World Monument Fund’s list of the ‘100 most-threatened heritage sites’ in the world. Murujuga was the first Australian site to be added to the World Monument Fund list. Despite this listing, the state and Australian governments have allowed industrial development to continue unabated and without meaningful restrictions on emissions into the atmosphere. Both levels of government insist that the petroglyphs and industry can coexist on Murujuga.

Bednarik, in 2011, expressed optimism that changes in the Western Australian and Federal government personnel and attitudes from ‘strong leaders’ would bring the required changes in government policies to limit further industrial development (Bednarik 2011). Such optimism, expressed again in 2013 (Bednarik 2013), has not eventuated with further development and high levels of acid forming emissions continuing on Murujuga.

Undeterred, Bednarik continues to advocate strongly for preservation of the world unique Murujuga petroglyphs. He wrote in despair that ‘despite the declaration of the Murujuga National Park, the industry and the cultural monument to the massacred Yaburara simply cannot coexist, because of the immense acidic pollution by industry. Since the rock art is immovable, it is essential that the industry be relocated’ (Bednarik 2017).

These same sentiments were recently expressed by Mulvaney (2022) ‘It cannot be clearer: for the Murujuga petroglyphs to survive, industrial emissions must be eliminated …… and any future industrial development has to be placed away from the Dampier Archipelago. Industrial representatives and those in government continue with the mantra of coexistence, but what has occurred in the last 50 years proves that 50,000 years of culture heritage can be unhesitatingly erased from existence.’

Conclusions

Bednarik and many others continue to ask themselves, why do Australian governments persist on placing industrial infrastructure among the petroglyphs of Murujuga and why do they not insist on reducing the permitted levels of emissions from industry to amounts that will not damage the petroglyphs?

Is it, as Ludlam (2021) may suggest in his book ‘Full Circle’, the governments are ‘Captured States’? Ludlam describes that, in a ‘Captured State’, the State regulatory agencies operate and legislate in accordance with the private interests instead of the public interests. Or, is the lack of respect for Murujuga petroglyphs, primarily a simple disregard of an ancient and ongoing culture of Australia’s original people-iconoclasm?

José Antonio González Zarandona (2020), a world expert in heritage destruction, has characterised this continued damage to the Murujuga petroglyphs as ‘landscape iconoclasm’, the intentional act to dishonour an entire belief system and supersede Western economic values above Indigenous living

spiritual values. He argues that the scarred industrial landscape of Murujuga, bulldozed for decades by industry, intentionally stamps visual confirmation that there are “victors and vanquished” in this landscape. Multinational industry over Aboriginal people, their culture and their heritage.

Landscape iconoclasm is another example of ‘othering’ described by Edward Said in his 1978 book ‘Orientalism’. Said describes ‘othering’ as ‘disregarding, essentialising, denuding the humanity of another culture, people or geographical region’. The concept is expanded by Naomi Klien (2019) in her book ‘On Fire’. Klein states that once the ‘other’ ‘has been firmly established, the ground is softened for any transgression: violent expulsion, land theft, occupation and invasion’. The ‘other’ simply does not have the same rights as those making the distinction. This description is exactly what has happened on Murujuga, but with a massacre of the population included (Gara 1983). Pursuing justice for the Murujuga petroglyphs and their custodians has been a lifetime pursuit of Robert Bednarik and his great efforts continue.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the intergenerational trauma experienced by the Traditional Owners of Murujuga and the adjacent Language Groups. We too, feel their pain from the ongoing senseless destruction of a magnificent culture for the sake of short-term financial gain and natural resource exploitation. We acknowledge also the enormous efforts by many including Traditional Owners, Tim Douglas, Wilfred Hicks and more recently the members of ‘Save Our Songlines’, Ken Mulvaney, Judith Hugo and FARA members, Gary and Glen Slee, Benjamin Smith and others in their ongoing endeavours to save the Murujuga petroglyphs for future generations. JLB is extremely grateful to the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation Board and Circle of Elders who, in 2016 and 2017, supported his proposal to raise money from the concerned public to conduct research into understanding the science relating to preservation of the petroglyphs through the Murujuga Rock Art Conservation Project.

Dr John L. Black AM

Warrimoo, New South Wales, Australia

E-mail: jblack@pnc.com.au

Hon Robin H. Chapple

Chapple Research, Derby, Western Australia

E-mail: chappleresearch@iinet.net.au

References

Bednarik, R. G. 1977. A survey of prehistoric sites in the Tom Price region, North Western Australia. Archaeology and Physical Anthropology in Oceania, 12: 51-76.

Bednarik, R. G. 1979. The potential of rock patination analysis in Australian archeology – part 1. The Artefact, 4: 14-38.

Bednarik, R. G. 1980. The potential of rock patination analysis in Australian archeology – part 2. The Artefact, 5: 47-77.

376 Study of Palaeoart of the World, John L. Black & Robin H. Chapple

Bednarik, R. G. 2002. The survival of the Murujuga (Burrup) petroglyphs. Rock Art Research, 19(1): 29.

Bednarik, R. G. 2004. Recipe for disaster. AURA Newsletter, 21 (1): 5-6.

Bednarik, R. G. 2006a. Australian apocalypse: The story of Australia’s greatest cultural monument. Occasional AURA Publication No. 14. Australian Rock Art Research Association, Melbourne.

Bednarik, R. G. 2006b. Quantification of the amount of rock art lost at Dampier. Rock Art Research, 23: 137–140.

Bednarik, R. G. 2007. The science of Dampier rock art – Part 1. Rock Art Research, 24 (2): 209-246.

Bednarik, R. G. 2011. The Dampier Campaign. Rock Art Research, 28 (1): 27-34.

Bednarik, R. G. 2013. Final victory at Murujuga imminent. Rock Art Research, 30 (1): 130-131.

Bednarik, R. G. 2017. Solving the Dampier controversy. Editorial, Rock Art Research, 34 (2): 126-129.

Black, J. L. and S. Diffey 2016. Reanalysis of the colour changes from 2004 to 2014 on Burrup Peninsula rock art sites, Report submitted to the Western Australian Government, Department of Environment Regulation

Black, J. L., I. Box and S. Diffey 2017a. Inadequacies of research used to monitor change to rock art and regulate industry on Murujuga (‘Burrup Peninsula’), Australia. Rock Art Research, 34(2): 130-148.

Black, J. L., I. D. MacLeod and B. W. Smith 2017b. Theoretical effects of industrial emissions on colour change at rock art sites on Burrup Peninsula, Western Australia. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 12: 457-462.

Data Analysis Australia, J. Henstridge and K. Haskard 2017. Review of CSIRO report of Burrup Peninsula rock art monitoring, Department of Environment Regulation, Western Australia. https://www.der.wa.gov.au/images/documents/our-work/consultation/Burrup-Rock-Art/DAA-independent-review-report-May-2017.pdf.

Gara, T. 1983 The Flying Foam massacre: An incident on the northwest frontier, Western Australia. paper presented to the Archaeology at ANZAAS 1983, 53rd ANZAAS Congress, Perth, Western Australia.

Gillett, R. 2008 Burrup Peninsula air pollution study: Report for 2004/2005 and 2007/2008, Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia.

González Zarandona, J. A. 2020. Murujuga: rock art, heritage, and landscape iconoclasm. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Klein, N. 2019. On Fire: the burning case for a green deal. Allen Lane part of Penguin Random House, UK.

Lau, D., E. Ramanaidou, S. Furman, A. Hacket, M. Caccetta, M. Wells and B. McDonald 2008. Burrup Peninsula Aboriginal Petroglyphs: Colour Change and Spectral Mineralogy 2004–2007, CSIRO. https://www.der.wa.gov.au/images/documents/our-work/programs/Colour_Change_and_Spectral_Mineralogy_2007_report_Sept2008.pdf.

Lorblanchet, M. 1983. Chronology of the rock engravings of Gum Tree Valley and Skew Valley near Dampier, WA. In: M. Smith (ed.), Archaeology at ANZAAS 1983. Western Australian Museum, Perth, pp. 39-59.

Lorblanchet, M. 1992. The rock engraving of Gum Tree Valley and Skew Valley, Dampier, Western Australia: chronology and functions of the sites. In: J. McDonald and I.P. Haskovec (eds), State of the Art: Regional Rock Art Studies in Australia and Melanesia. AURA Publication, Melbourne, pp. 39-59.

Petroglyphs on Murujuga, Western Australia-Unique, Endangered… John L. Black & Robin H. Chapple 377

Lorblanchet, M.2018. Archaeology and petroglyphs of Dampier (Western Australia): An archaeological investigation of Skew Valley and Gum Tree Valley. Technical Report of the Australian Museum, Number 27. Doi.org/10.3853/j.1835-4211.27.2018.

Ludlam, S. 2021. Full Circle: a search for the world that comes next. Black Inc., Schwartz Media, Carlton, Victoria Australia.

MacLeod, I. 2005. Effects of moisture, micronutrient supplies and microbiological activity on the surface pH of rocks in the Burrup Peninsula. Triennial meeting (14th), The Hague, 12-16 September 2005, pp. 386-393. James & James, London.

Markley, T., M. Wells, E. Ramanaidou, D. Lau and D. Alexander 2015. Burrup Peninsula aboriginal petroglyphs: Colour changes & spectral mineralogy 2004-2014. CSIRO, Australia. Report EP1410003. https://www.der.wa.gov.au/our-work/programs/36-burrup-rock-art-monitoring-program.

Mulvaney, K.J. 2022. Without them – what then? People, petroglyphs and Murujuga. In: (Eds. Tacon, P.S.C, May, S.K., Frederick, U.K., McDonald, J. ‘Terra Australis 55: Histories of Australian Rock Art’ Chapter 9, p155-172. http://doi.org/10.22459/TA55.2022

O’Hara, G. 2008 Monitoring of microbial diversity on rock surfaces of the Burrup Peninsula. Monitoring of microbial diversity on rock surfaces of the Burrup Peninsula. https://web.archive.org/web/20091002135201/http:/www.dsd.wa.gov.au/documents/Microbial_Diversity_on_Rock_Surfaces_-_Sept2008(1).doc.

Said, E.W. 1978. Orientalism. Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. London.

Slee, G. 2022. Stompers. Classic Slee Pty Ltd. Karratha, Western Australia.

Smith, B.W., J.L. Black, S. Hoerlé, M.A. Ferland, S.M. Diffey, J.T. Neumann and T. Geisler 2022a. The impact of Industrial pollution on the rock art of Murujuga, Western Australia. Rock Art Research 39: 1-14.

Smith, B.W., J.L. Black, K.J. Mulvaney S. Hoerlé 2022b. Monitoring rock art decay: Archival images of petroglyphs on Murujuga, Western Australia. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites. Online: DOI: 10.1080/13505033.2022.2131077: https://doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2022.2131077

Vinnicombe, P. 2002. Petroglyphs of the Dampier Archaepilago: Background to development and descriptive analysis. Rock Art Research, 19(1): 3-27.

Virili, F.L. 1977. Aboriginal sites and rock art of the Dampier Archipelago. In: P.J. Ucko (ed.) Form in Indigenous art: Schematisation in the art of Aboriginal Australia and prehistoric Europe, pp. 439-451